With reports of the first human death from bird flu in the US, some Americans are feeling an uncomfortable flashback to the early days of Covid-19, when infectious disease experts were talking about a new virus that was sending people to the hospital with respiratory infections. Although both viruses can cause breathing problems, they are very different.

Covid was spreading easily from person to person when it arrived in the US in 2020, but bird flu has been lurking for years, mostly as a problem for animals. Scientists also know a lot more about H5N1 bird flu than they did the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and the US has been preparing for the threat of a new flu outbreak for a long time.

Still, the virus is making moves that deserve attention. Here’s what you need to know about H5N1.

What is bird flu?

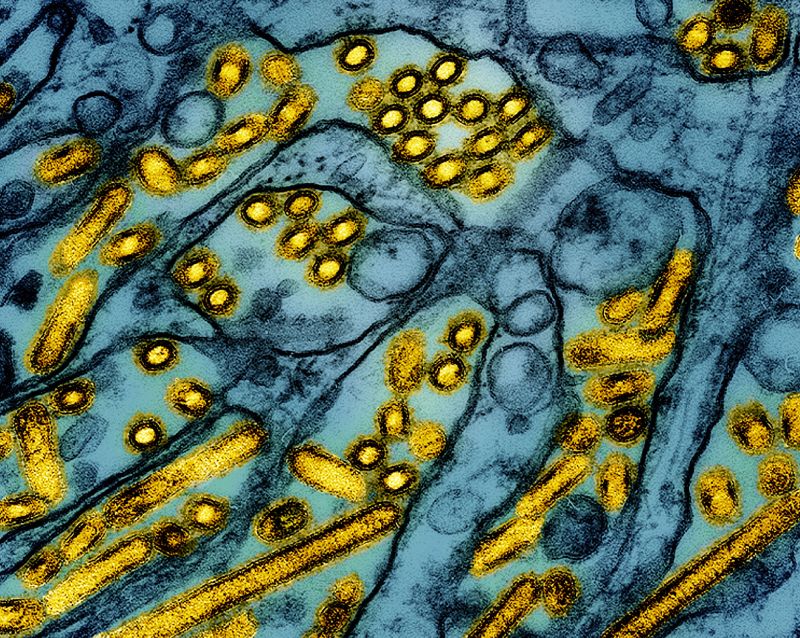

Avian influenza, or bird flu, is a broad term that refers to several types of influenza that normally infect birds. The bird flu that’s been making news in the United States is a virus called H5N1.

Some flu viruses carried by birds cause only mild infections and are classified as low-pathogenic viruses. In contrast, H5N1 often kills birds that catch it, so it is classified as a highly pathogenic avian influenza.

To complicate matters, although bird flu viruses primarily prey on birds, they can also spread to other animals, including humans. Human infections with bird flu viruses are rare, and they’re usually what scientists call dead-end infections because they don’t typically transmit from person to person.

Is H5N1 a new virus?

You may have heard of H5N1 only recently, but it’s not a new virus. Scientists have been tracking it for almost three decades.

It was first identified in geese in Southern China in 1996. Over the years, it has caused sporadic outbreaks in wild and farmed birds around the globe.

The virus reappeared in North America in late 2021, and it quickly caught scientists’ attention because it seemed to have broadened its repertoire, spreading beyond birds and infecting a growing variety of mammals. In the current wave of infections, it has spread to more than 48 species in at least 26 countries.

It has caused mass die-offs of marine mammals too, including 24,000 sea lions that died in South America in 2023. In February 2024, Dr. Jeremy Farrar, who is chief scientist at the World Health Organization, called the ongoing spread of H5N1 “a pandemic of animals.”

Since 2022, more than 130 million wild and farmed birds have been affected in America across all 50 states, 919 dairy herds have tested positive in 16 states, and 66 people have tested positive in 10 states, according to data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the US Department of Agriculture.

Could H5N1 become a new pandemic?

Scientists agree that the virus would need to evolve – or retain key changes in its genetic sequence – to start a pandemic.

Each time a virus infects a cell and copies itself, it makes mistakes. Usually, these mistakes are benign or even harmful for the virus, but occasionally, there’s a genetic change that helps the virus become better at infecting cells. Given the right set of circumstances, that version of the virus may outcompete others and continue to survive, going on to infect new hosts or new kinds of hosts.

Flu viruses can change in another way, too

Each virus has eight segments, and like kids in a lunch room, they are always looking to swap. When two viruses trade whole segments, it’s called a reassortment, and it result in quick and sometimes dramatic changes to a virus’ abilities.

Scientists say either type of change could spell trouble for humans. Although the H5N1 virus is very good at infecting birds and has become a threat for many different kinds of mammals, including dairy cows, it’s still pretty clumsy at infecting people.

In cows, for example, the H5N1 virus primarily infects the mammary glands. This causes a dramatic drop in milk production but usually doesn’t kill the cow. In people, the main route of infection seems to be through the eyes; conjunctivitis, or red, inflamed eyes, seems to be the telltale symptom of infection.

Scientists think H5N1 infects the eyes because flu viruses enter cells through sugars on their surface called sialic acids. Birds – and human eyes – primarily have alpha 2,3 sialic acid receptors on their cells. But a different kind of sialic acid receptor, alpha 2,6, is more prevalent in the human respiratory tract. Human flu viruses, including those that cause seasonal influenza, have evolved to infect cells through alpha 2,6 receptors.

Given enough time in the human body, the bird flu virus has shown the ability to change to become better at infecting different kinds of cells and tissues, spreading from the eyes to the respiratory tract, for example.

Researchers detected key changes to the genome of the virus in teenager in Canada who became severely ill with H5N1 in November. Those changes probably helped it infect cells in her respiratory tract. Samples of the H5N1 virus that infected a severely ill patient in Louisiana also showed signs of adaptation to human cells. Infectious disease experts warn that as the virus continues to spread, it’s more likely that it changes to become a fully human pathogen.

How are people catching bird flu?

When humans have become infected, it’s almost always through contact with infected animals. Nearly all of these so-called spillover infections have been mild. And no one who has gotten H5N1 in the US is known to have given the infection to anyone else.

How do we know it’s not spreading from person to person?

The CDC and state public health departments are monitoring farm workers who test positive and following everyone they’ve been around while ill, a practice called contact tracing, to see if they get sick. State public health labs are also sequencing all influenza A viruses detected through routine flu testing. So far, only two bird flu infections in people have been detected this way.

The CDC estimates that the current risk to the public is low.

How do I get tested if I think I have bird flu?

If you become ill within 10 days of contact with sick or dead animals or their droppings, make sure to alert a health care provider to your exposure.

Although most of the H5N1 samples have been handled by the state public health laboratory system, the CDC has been working to expand testing, and large commercial laboratories such as Quest and Labcorp now have tests that can detect H5 viruses.

That means it is easier for doctors to test patients if they suspect a bird flu infection.

Who is at risk from bird flu?

The two groups of people who are most at risk are dairy and poultry workers and people who have backyard bird flocks, said Dr. Michael Osterholm, who directs the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota.

The virus homes in on the udders of milking cows, and studies have found high concentrations of bird flu virus in raw milk.

The milking parlors of dairies are wet environments, and workers can be infected if they get a splash of raw milk in their eyes or if they get milk on their hands and then rub their eyes. Droplets of virus-laden milk can also become airborne if they spray from milking equipment.

Birds shed the virus through their saliva, mucus and feces, and it can become airborne when their litter and feathers are churned up in barns, particularly during culling operations.

“It can be in the air,” Osterholm said. “So it’s not even just contact touching the birds, but just the dander and all the dust that occurs when you’re dealing with birds.”

What are the symptoms of bird flu?

One of the most prominent symptoms in infected farm workers has been red, irritated eyes. A recent study of the first 46 human cases in the current outbreak in the US found that 93% had conjunctivitis.

For about a third of the total, that was their only symptom. The second most common symptom, experienced by about half of infected farm workers, was a fever. About a third of people with H5N1 had respiratory symptoms, but these were most common among poultry workers who were exposed during bird depopulation activities.

Two people in North America have had severe infections. The first was the 13-year-old girl in Canada, who became critically ill with lung and kidney failure and was put on life support for two weeks to give her organs time to recover. It’s not clear how she was exposed to the virus.

The second person, from Louisiana, was hospitalized with severe respiratory symptoms after exposure to a backyard flock and wild birds. That person, who was over age 65 and had underlying medical conditions, died this month, becoming the first death in the US from bird flu.

Both of these patients had the D1.1 strain of the virus, which is circulating in wild birds. It’s different from the B3.13 virus that has been infecting workers on dairy farms. Researchers are investigating whether the D1.1 strain might cause more severe disease.

Can you get bird flu from milk or meat?

Milk and meat that have been heated to kill germs are safe.

Even before H5N1 was a consideration, health officials cautioned against drinking raw milk or eating undercooked meat because both can harbor nasty germs like salmonella and E. coli. Cats have died from drinking raw milk on farms.

- Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Friday from the CNN Health team.

Studies by the US Food and Drug Administration show that common pasteurization methods neutralize the virus, but refrigeration doesn’t. USDA studies show that cooking meat to a safe temperature inactivates the virus.

A recent study from Stanford University that involved lacing raw milk with flu virus and then testing it on cells in a lab found that the virus could still infect cells for up to five days after being refrigerated.

No human infections have been linked to raw milk consumption, although a toddler in California recently tested positive for the flu after drinking a large amount of raw milk. The CDC wasn’t able to confirm the infection, so this child is listed as a suspected case.